17. Patton’s Pets and Other Epithets

761st Tank Battalion crew in 1944.

This is what I have come to understand: If you are a white person, racism is worse than you think. Even if you hold enlightened views on race, even if you’re horrified by the rise of white supremacy, police brutality, the school-to-prison pipeline. And so on. Systemic racism, individual racism, historical racism – not only worse than you think but worse than you can possibly imagine. Acknowledging this in any but the most abstract way is an ongoing process.

On the Army posts where I grew up, military rank outranked race in the social hierarchy. And because the military was desegregated in 1948, I went to integrated schools during my childhood. Nothing I could see around me seemed too unfair.

Since then, that perspective has been challenged many times in many ways. Here is a story about one of them: After I became a journalist, I often wrote about the military. When the New York Times Magazine planned a special issue to commemorate the 50th anniversary of World War II, I was asked to do a series of oral history interviews with Black veterans. I was excited by this assignment, my first for the Magazine. It didn’t occur to me to wonder why a white journalist had been chosen for the job.

The veterans I found to interview – a Marine, a Tuskegee Airman, a platoon sergeant in a tank battalion, a sailor on a destroyer escort – were among the elite minority of Black military men who were allowed to serve in combat units. They each told me of their belief that if they acquitted themselves honorably in battle, they would come home to a changed America, that the barriers against them would fall. As Lorenzo Dufau said, “If I can help get rid of Hitler and protect my home, and help break down that racial barrier, I'll be doing a service for the country and trying to make it better for when my child grows up, and others like him. Doors will open."

It was heartbreaking and infuriating to think about how such hopes had been betrayed – especially when I came to understand how hard the men I interviewed had had to fight just to get into the fight.

The history of the 761st Tank Battalion by Trezzvant Anderson was published in 1945. Anderson later joined the Pittsburgh Courier and covered the Civil Rights movement.

One of them, Johnnie Stevens, was a member of the 761st tank battalion, which fought across Europe for an unheard-of duration – six straight months without relief – liberating some 30 towns in France. Stevens and his fellow Black tankers had completed advanced training in Texas, but there was, he said, no intention of sending “this Black outfit” into combat.

“Then,” he told me, “General Patton came into the picture. He watched us train and decided he wanted us.” At first Roosevelt refused, but Patton took his case to Eleanor – who interceded with Franklin. “That’s how we ended up in the Third Army.” Not everyone was pleased about this development. As Stevens told me, “They called us ‘Patton’s pets and Eleanor’s niggers.’”

I admired Johnnie Stevens and the other men I interviewed and hoped that when the story was published some belated recognition and respect might come their way. But when I got a copy of the galley proofs I was horrified. The Times Magazine had a new editorial director who’d been brought in to liven it up, make it more edgy. He’d had the brainstorm that a phrase from Johnnie Stevens’ quote would make a catchy headline for all the oral histories. It was already set in type on the contents page: “‘Patton’s Pets and Eleanor’s Niggers,’ As Told to Ann Banks.”

Plucked from its context and presented without attribution, this headline struck me as beyond offensive. I could only imagine how betrayed the men I had interviewed would feel when they saw it. I pleaded with the story editor to change the title. She was Black herself and I thought she would agree that this was wrong.

She did. She had tried to get it changed herself – and failed. She told me it was too late. The contents page was already set in type and the whole thing would have to be reset. It would be too expensive. There was no point in taking the case to higher-ups because I wouldn’t get anywhere.

I decided I had to try – even if it meant never writing for the Times again. I managed to reach around the editorial director to Jack Rosenthal, the legendary New York Times journalist who held the title of editor of the Magazine. As I explained my position to him, I had the sense that he also was uncomfortable with the headline.

I imagined that it had been foisted on him in the spirit of “edginess.” Even so, he regretted to tell me, it was indeed too late to make a change, it would just be too expensive. Thanks to my journalist friend Walter Shapiro, who had rehearsed the call with me ahead of time, I was ready with my line: “Mr. Rosenthal, some things are more important than money.”

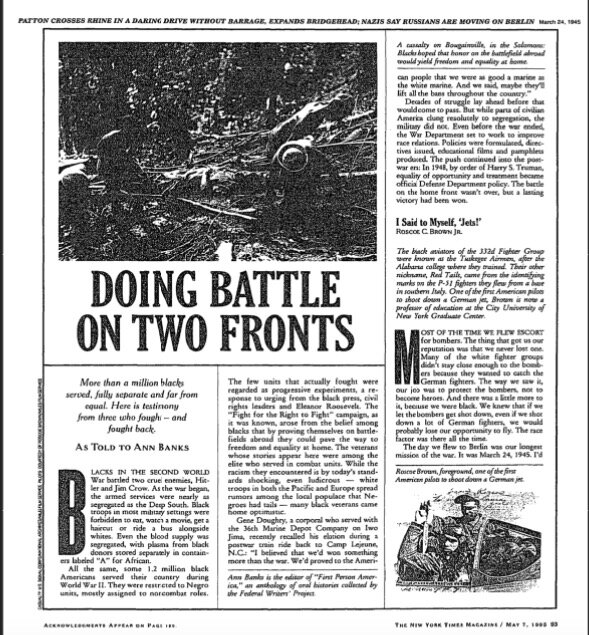

I’m glad to report that it worked. My article was published on the anniversary of World War II under the headline, “Doing Battle on Two Fronts, As Told to Ann Banks.”

I did write for the Times again, and on a similar subject. Under the headline “Jim Crow’s Last War,” I reviewed a book called Blood for Dignity, by David Colley, about the first integrated combat unit in the U.S. Army. It was a familiar story. Again young Black men volunteered for front line combat and encountered resistance from the top brass. Again Eleanor Roosevelt played a role in taking up their cause. With the Army running low on foot soldiers, General Eisenhower decided to form all-Black infantry platoons under the command of white officers. These platoons gained a well-deserved reputation for fierceness in battle, yet they are scarcely mentioned in the popular chronicles we take as true.

The mythologizers of World War II not only have played down the disrespectful treatment of Black troops but also have largely neglected to invite Black veterans to the victory party. As I wrote in my review, “As we shape our stories, so do our stories shape us.” That is why it is important to tell those stories fully and truthfully.

The Stars and Stripes headline.

Cpl. Carlton Chapman, a machine gunner with the 761st in France .

761st Tank Battalion, company A.