In a 1965 essay in Ebony magazine, James Baldwin argued that every white American needs to confront honestly the nation's true history. Failure to do this “hideously menaces this country,” he wrote. Baldwin seemed almost to foresee the mob violence on horrifying display at the United States Capitol on Jan. 6 — the noose hung from a gallows, the sea of MAGA hats and Confederate flags.

The Congressional hearings into the uprising demonstrated, among other things, that ongoing veneration of the Confederacy feeds into extremist violence. The insurrectionists in the Capitol harked back to the true believers in the South after the Civil War, for whom it was an article of faith that the South would rise again. The Lost Cause narrative, as it came to be known, was a wildly successful propaganda campaign to portray the South as the War’s moral victors. This white supremacist myth has flourished for more than 150 years, one family story at a time. As such lies get passed along, so they must be undone.

I started Confederates in My Closet to challenge those stories in my own family — and in myself. I did not have to look far for evidence of our complicity in perpetuating the lie of the Lost Cause. For decades I harbored in the far reaches of my office closet an archive I inherited from my father’s Alabama kin.

Ransacking these archives, I turned up grifters, slavers, murderers and the woman whose counterfeit letters ennobled General George Pickett. Investigating a mystery name engraved on a spoon from my silverware drawer, I encountered the man who issued the order to attack Ft. Sumter – a cousin by marriage – and who famously prophesied that the Civil War would shed no more blood than could be soaked up by his handkerchief.

I dove into the rancorous debate over the correct translation of the Confederacy’s motto. (Does “Deo Vindici” mean “A vengeful God” or “With God as our champion”?) I traced the uncanny link between John Brown and John Wilkes Booth. And I found an abolitionist, a great uncle, who at the 1860 Republican convention, nominated Abraham Lincoln for President.

These are stories of a past that is not past. The contested history they evoke is the landscape of the political battles we are living through right now. Facing this history is one path to a more just society. That is what I hope.

Confederates in my closet: ESSAY 0

How I got into this

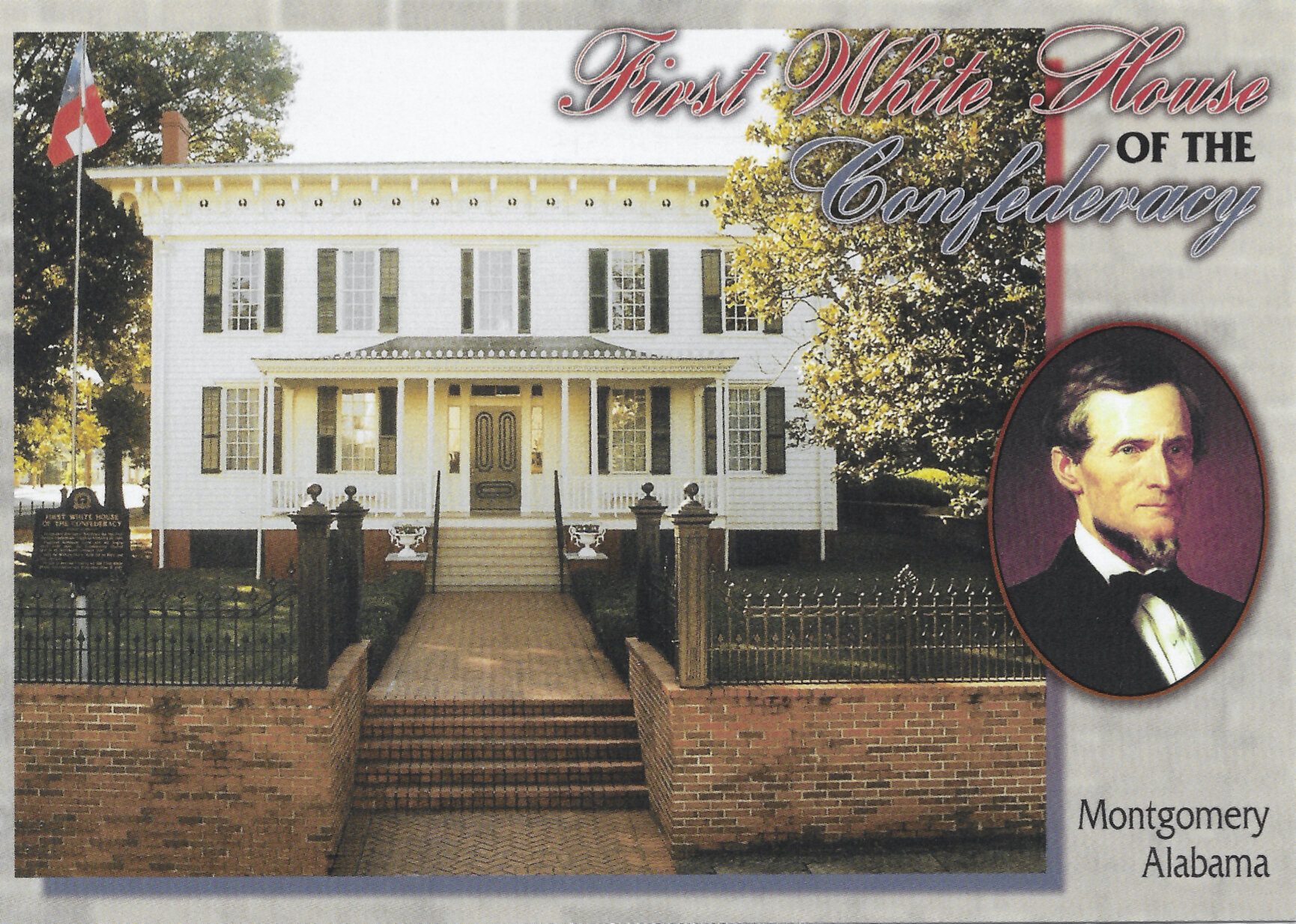

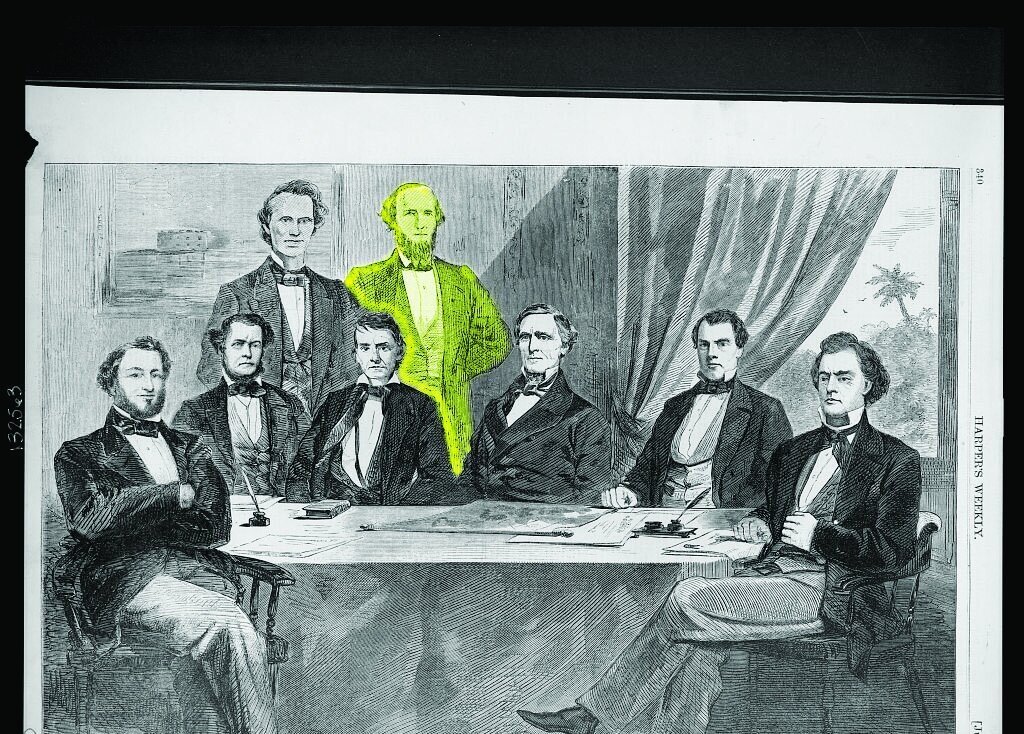

For decades I harbored in the back of my office closet an archive I inherited from my father’s Alabama kin. Wills bequeathing family oil portraits; yellowed newspaper clippings about antebellum homes-turned-museums; hand-drawn genealogical charts, held together with rusty paper clips, tracing my connection to high-profile Confederates from Gen. George Pickett to L.P. Walker, the first Secretary of War of the Confederacy. I nicknamed this trove “The Pile” and for years I kept it in quarantine. If these bits and pieces told a story, I wasn’t ready to hear it.

The idea that facing history is a path to justice has been advanced by Black thinkers from James Baldwin to Ta-Nehisi Coates to Bryan Stevenson. For a long while I resisted it, at least when it came to my own family. For a long while I believed that the Civil War was over. I knew it had a huge fan base – from the hobbyists who reenact favorite battles to history buffs who debate the fine points of military strategy. When I encountered members of these fervent and possessed subcultures on the Internet, I always felt like I was walking along the edge of a tar pit. I didn’t want to get too close.

Then, after the 2016 election, the Civil War came for me, and there was nothing quaint about it. As a reinvigorated white supremacy began sweeping the country, I knew it was time to take the Confederates out of the closet.

confederates in my closet: essay 1

The Mystery of the Great Seal

This is the story I remember being told as a child: At the time of the Civil War, there was cast in solid gold a Great Seal of the Confederate States of America. Toward the end of the war, to keep the seal from falling into the hands of Yankees, it was buried somewhere in Virginia. Somehow its location was lost and the Great Seal has never yet been found. At the time it was cast, however, four smaller replicas of the seal were made, also of gold. One of these replicas was handed down in my family until it came to my father…

confederates in my closet: essay 2

Southerner in Denial

Twenty years ago white filmmaker Macky Alston set out to find his black cousins. Macky’s great great great great uncle was “Chatham Jack” Alston, the largest slaveholder in North Carolina and the brother of my own great great great great grandfather, also a slaveholder, Philip Alston. Macky wanted to face this legacy and understand its meaning for the present.

When I first saw Family Name, I was motivated to delve, ever so briefly, into my own family’s Alston connection…

confederates in my closet: essay 3

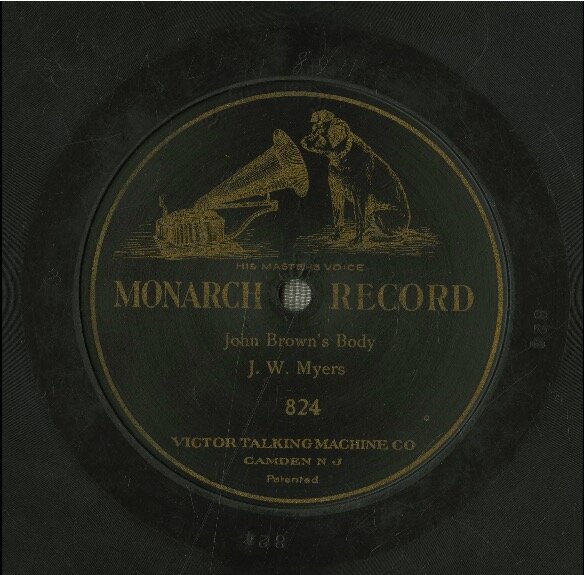

“John Brown’s Body”

What to think about John Brown? There’s no question that his audacious invasion of Harpers Ferry and his subsequent execution helped ignite the Civil War. On the other hand, you might think him a nut. His raid was underprepared and beyond foolhardy and numbers of his followers of both races lost their lives. One of the dead was his own son. Reading Midnight Rising, Tony Horwitz’s book about John Brown, I started taking down the adjectives Horwitz uses to describe his subject: domineering, grandiose, zealous, obstinate, righteous, fanatical, blustering, unflinching, brazen, unbending, outrageous, outlandish.

confederates in my closet: essay 4

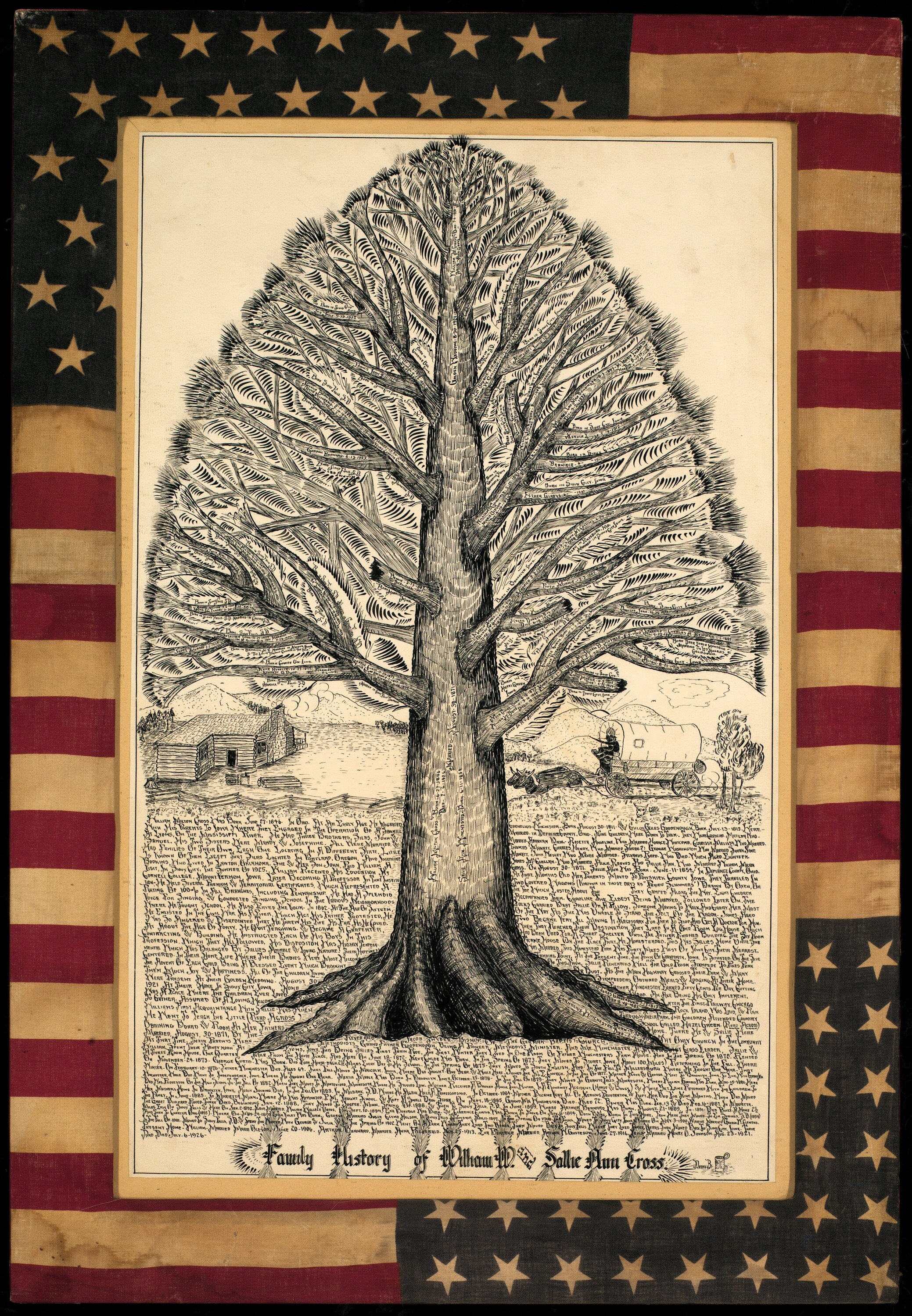

The Seductions and Confusions of Genealogical Research

What started as an idle pastime – googling my father’s name – produced several surprises. It was of no particular consequence to learn that my great great grandfather may have been born out of wedlock. But I was shocked to come across the information that he had owned 7 slaves. I expected that my planter ancestors would have been slaveholders, but my great great grandfather was a doctor. I have since learned that households owning small numbers of slaves was not unusual: nearly half of the Southerners who owned slaves held fewer than five.

confederates in my closet: essay 5

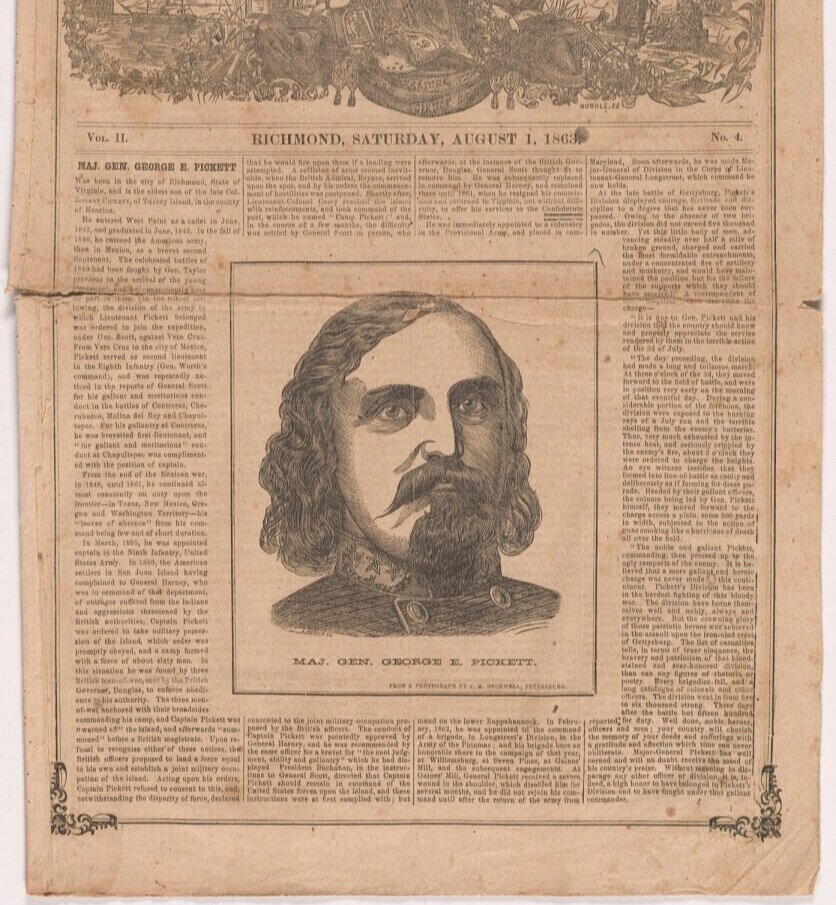

The Cult of the Lost Cause and the Invention of General Pickett

George Pickett – Major General George E. Pickett – was our family’s marquee Confederate relation, distant cousin though he was. Everyone in America has heard of him, thanks to the ill-fated infantry charge at the Battle of Gettysburg. For a long time what I knew about him was pretty much what everyone learned in 8th grade: Pickett’s failed charge, on July 3rd, 1863, was the turning point, the moment when the Confederates started to lose.

Confederates in my closet: essay 6

Look Away

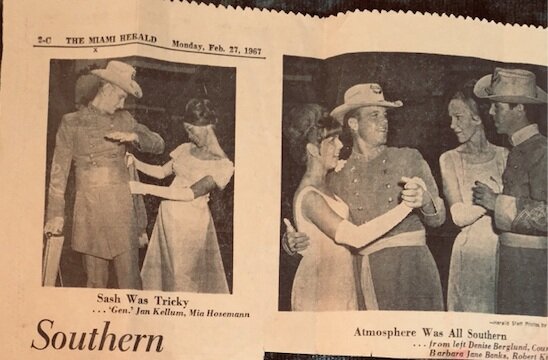

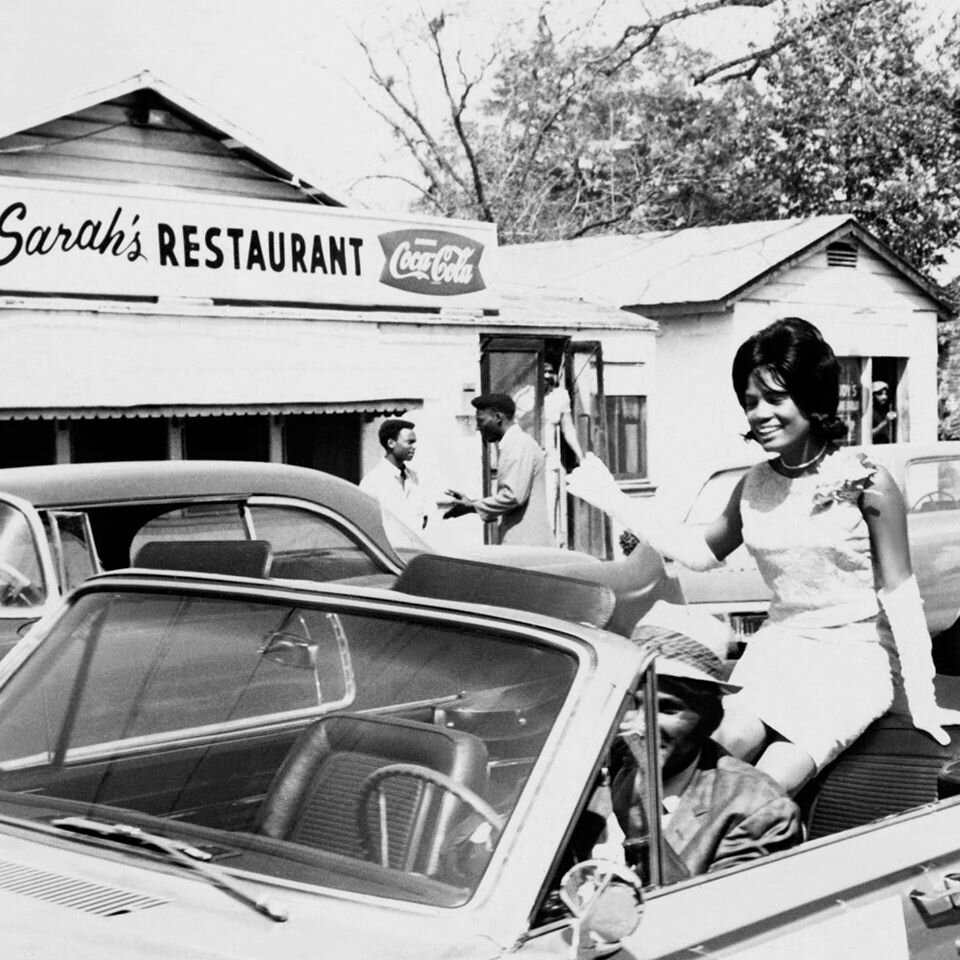

I recall precious little about the night my sister made her debut with the Society of Southern Families – which attests to the astonishing power of disassociation. I was there and yet I wasn’t – a Stepford sister in very reluctant attendance. That this improbable event really happened is confirmed by a clipping from the Miami Herald that I’ve found in the pile of hand-me-down family documents in the back of my office closet: The headline reads “Southern Debs Bow in Splendor.”

confederates in my closet: essay 7

The Unrightable Wrong

Should descendants of slave-holders feel ashamed of their ancestry? This is the issue raised by Glen David Andrews, a Black trombonist from New Orleans. I’d come to know Glen David when a filmmaker friend and I were researching a documentary about him. That project came to nothing, but I still follow him on Facebook, where he has been outspoken on many issues and not shy about schooling those he thinks need correction.

confederates in my closet: essay 8

Bless Your Heart, I do think you are lucky no one has shot you

When my friend Tammy saw my copy of the Great Seal of the Confederacy, the first thing she noticed was the motto: Deo Vindice. “A vengeful god,” she said. “Them southerners really know how to hate, don’t they?” Tammy is from a slaveholding, plantation-owning family herself; she is the one who brought me into Coming to the Table. It was some time after this that I stumbled across the thorny thicket of how exactly the Latin phrase should be translated – with some contending that the true meaning confers God’s blessing on the Southern cause. Not being a Latin scholar, I have no opinion on this. But perusing some of the comments on the internet, I have to think that Tammy has a point.

confederates in my closet: essay 9

The Confederate in my Silverware Drawer

Leroy Pope Walker first claimed my attention not from The Pile in my closet but from my silverware drawer, where his name is engraved on a silver serving spoon: “L.P. Walker to Eliza.” It kept company in the drawer with another serving spoon, this one engraved “Corinne to Eliza.” I knew these were family names, but that was all.

confederates in my closet: essay 11

L.P. Walker: The Historic Markers, the Play, the Cemetery Walk

My cousin-by-marriage, the first Secretary of War of the Confederacy, did not have a good war. That much was clear. But I also discovered that in post-war Alabama he played his part in what I believe is the greatest feat of the Confederate South: turning the losers into winners.

confederates in my closet: essay 11

My Great Grandfather, Stephen Douglas and the Seductions of Non-intervention

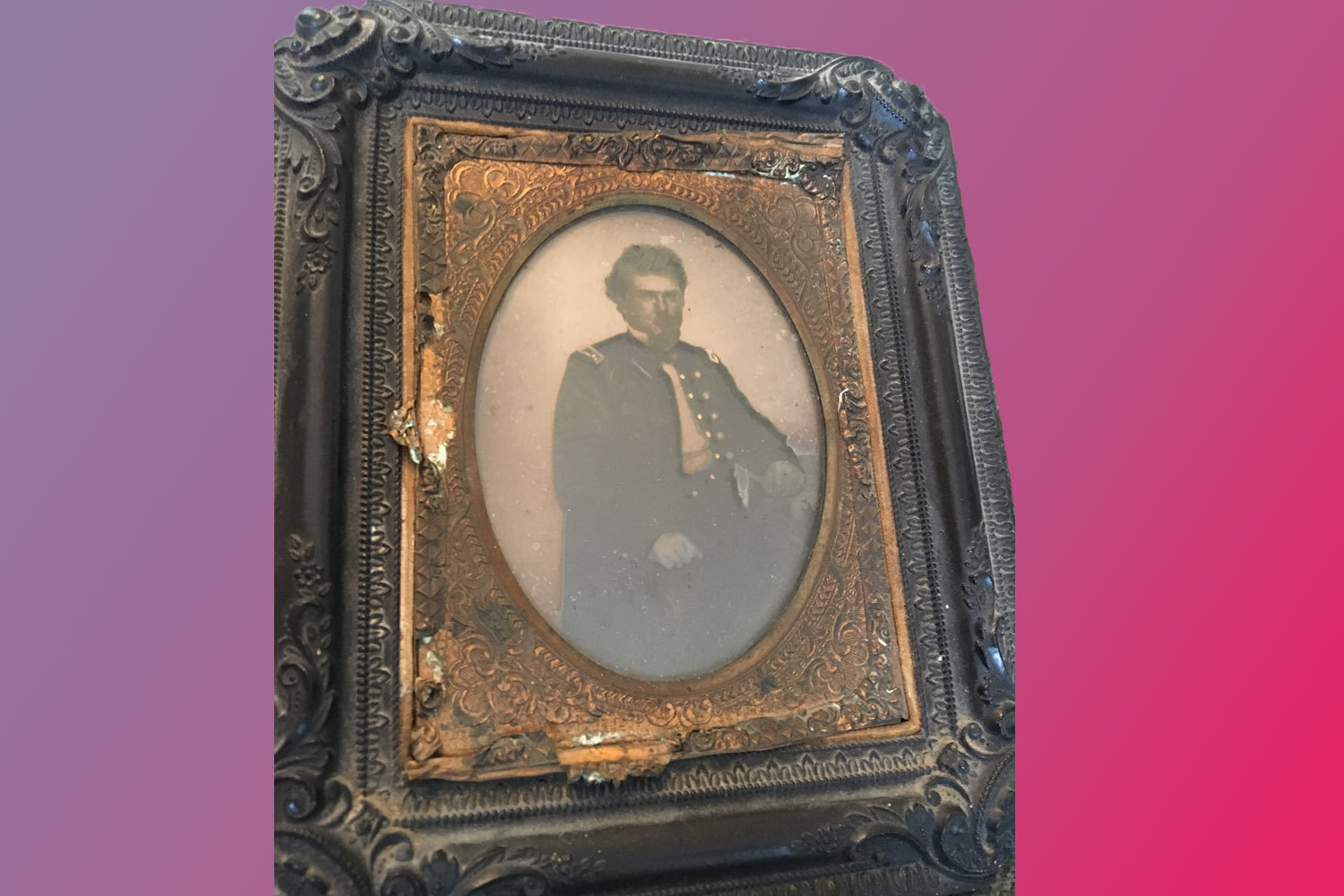

My decades-long lack of curiosity about the inscriptions on my silver spoons was no isolated lapse… In the days before Etsy, I used to frequent funky antique shops, and a tintype I have is the just sort of thing I might have bought as an item of décor. Only I didn’t. I inherited it – and am finally taking it in that the man in the photo is my own great grandfather, Edwin Alexander Banks.

confederates in my closet: essay 12

How to Change History

There is little doubt that in the audience on the statehouse steps on the day Stephen Douglas spoke was John Wilkes Booth. Booth would have been cheering as Douglas put before the citizens of Montgomery the case for remaining in the Union. The actor had arrived in town a week earlier to make his debut as a leading man, in the title role of Richard III.

confederates in my closet: essay 13

The Book and the Spoon

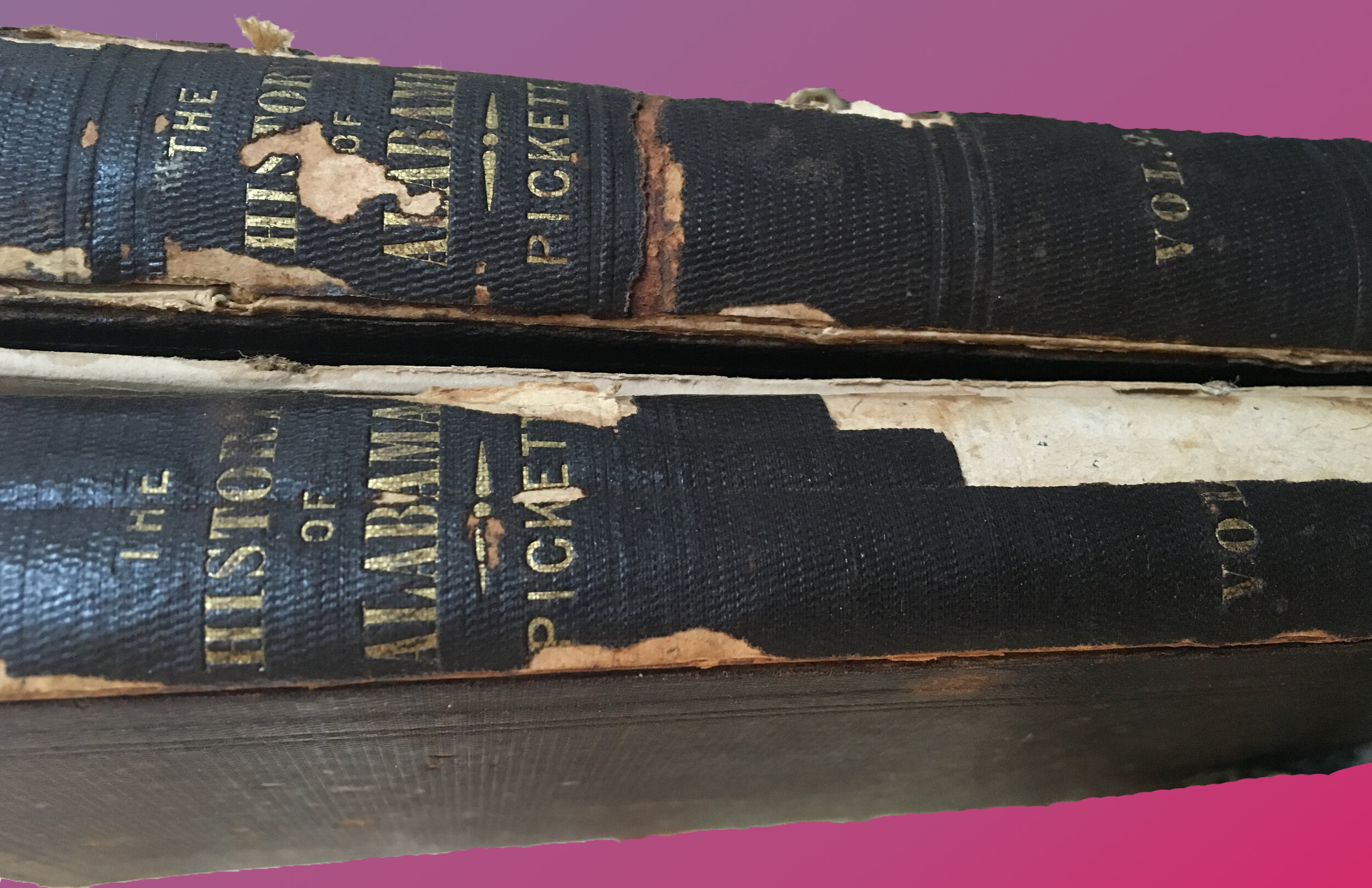

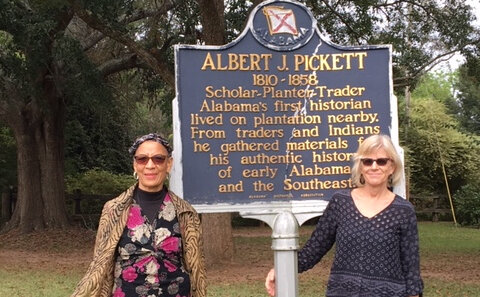

My method, if you can call something so haphazard a method, has been to start with a document from The Pile, or an artifact within the walls of my apartment, and follow it until it leads to a story. Sometimes unexpected connections reveal themselves, as between a tattered two-volume history of Alabama, published in 1851, and the “LP Walker to Eliza” silver serving spoon passed down to me. Leroy Pope Walker was the first Secretary of War of the Confederacy; I’ve written about him previously. Eliza was Eliza Dickson Pickett, Leroy’s wife as well as the niece of Albert James Pickett, usually referred to as “Alabama’s first historian.” He is the author of the tattered volumes.

A.J. Pickett is also my great-great-grandfather.

confederates in my closet: essay 14

“Mild Domestic Slavery”

A.J. Pickett may have been an author and historian with a house in Montgomery but I learned that he was equally a businessman with two plantations under his control. The ‘peculiar institution’ of slavery,’ as it came to be called, was essential to his life and to his work. By the time he was 30, my great-great-grandfather controlled more than 80 slaves. Some of this wealth came from marrying Sarah Smith Harris, who inherited a plantation of her own. Pickett appreciated her as his junior partner in slave management, as is clear from letters the couple exchanged while A.J. was away. Sarah described how she had taken action because the slaves did not have adequate meat. He replied that he was “glad you sent the bacon to the negroes for if I had been at home I would have done exactly as you did.”

confederates in my closet: essay 15

The Burden of the Pile

For years the contents of The Pile I’d inherited gathered dust in my closet, shut away, easy to ignore. Occasionally the thought would cross my mind that I should take out the papers and go through them – possibly sometime after I had finished alphabetizing my library, organizing my box of snapshots and culling my work files. Never, in other words.

confederates in my closet: essay 16

The Yankees are Coming! Hide the Silver!

Although The Pile offers no documentation of abducted families sold into slavery, there is abundant evidence of plantation-derived wealth. Stories about dwellings: Greek Revival plantation great houses, antebellum colonial mansions in town, a wood frame Revolutionary era house pocked with centuries-old bullet holes. The Pickett residential arrangements alone are described in no fewer than five accounts I find in The Pile.

confederates in my closet: essay 17

Patton’s Pets & Other Epithets

This is what I have come to understand: If you are a white person, racism is worse than you think. Even if you hold enlightened views on race, even if you’re horrified by the rise of white supremacy, police brutality, the school-to-prison pipeline. And so on. Systemic racism, individual racism, historical racism – not only worse than you think but worse than you can possibly imagine. Acknowledging this in any but the most abstract way is an ongoing process.

On the Army posts where I grew up, military rank outranked race in the social hierarchy. And because the military was desegregated in 1948, I went to integrated schools during my childhood. Nothing I could see around me seemed too unfair. Since then, that perspective has been challenged many times in many ways. Here is a story about one of them…

confederates in my closet: essay 18

Where am I From Again?

Where am I from? Growing up, that question always confounded me. I remember once being sent away for a week to a summer camp where I knew no one. My parents were busy relocating from one Army post to another, and the idea was it would be better for all if I was out of the way during the move. At the get-acquainted assembly the first night of camp, the counselor asked how many of us campers were Yankees. I didn’t exactly know what a Yankee was but the girl next to me raised her hand so I did too. It turned out there were only four of us; the camp was somewhere in the deep South. After all the other campers belted out Dixie, we four Yankees were made to get up on stage and sing “Yankee Doodle.”

confederates in my closet: essay 19

A Murderer in the Family

How long ago does a murder have to have taken place for the murderer to be described as “colorful?” It appears that my great great great great grandfather Philip Alston lived long enough ago to qualify. Alston, born in 1745, was a piece of work. I knew that even before I started excavating The Pile. My father was usually not one to make much of his ancestors, yet when we were stationed at Ft. Bragg, North Carolina, he took us on a family outing to visit the nearby Alston homestead, called The House on the Horseshoe. Attendance mandatory. I was home from college and had better things to do with my time, but in the end I was glad I went.

confederates in my closet: essay 20

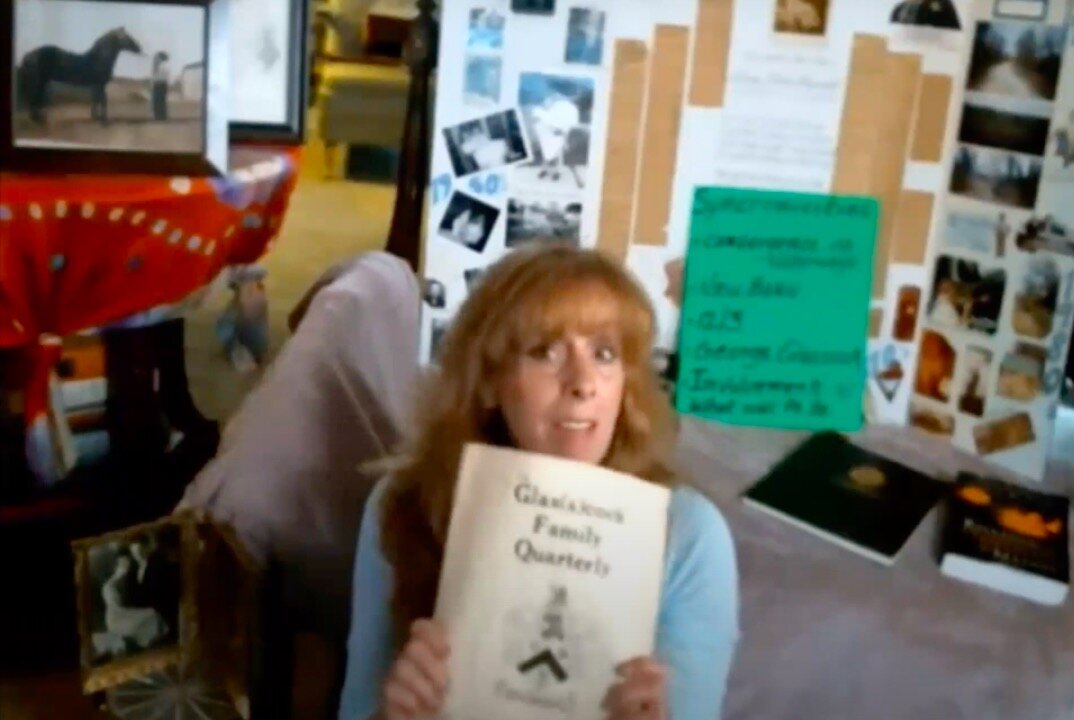

Did He Get Away?

An uncanny thing happened one afternoon when I was idly surfing the Internet looking for information on my great great great great grandfather Philip Alston’s murders – both the one he committed as well as his own murder. I came across my opposite number – my opposite number, that is, if I believed in curses and spiritualism and other non-observable phenomena. Suz Pratt, from Ferguson, Missouri, is a descendant of George Glascock, the man Philip Alston murdered. She too is obsessed with the story behind this long-ago crime, though as a “spiritual researcher” she has access to channels not accessible to me.